Launch by Andrew Jakubowicz

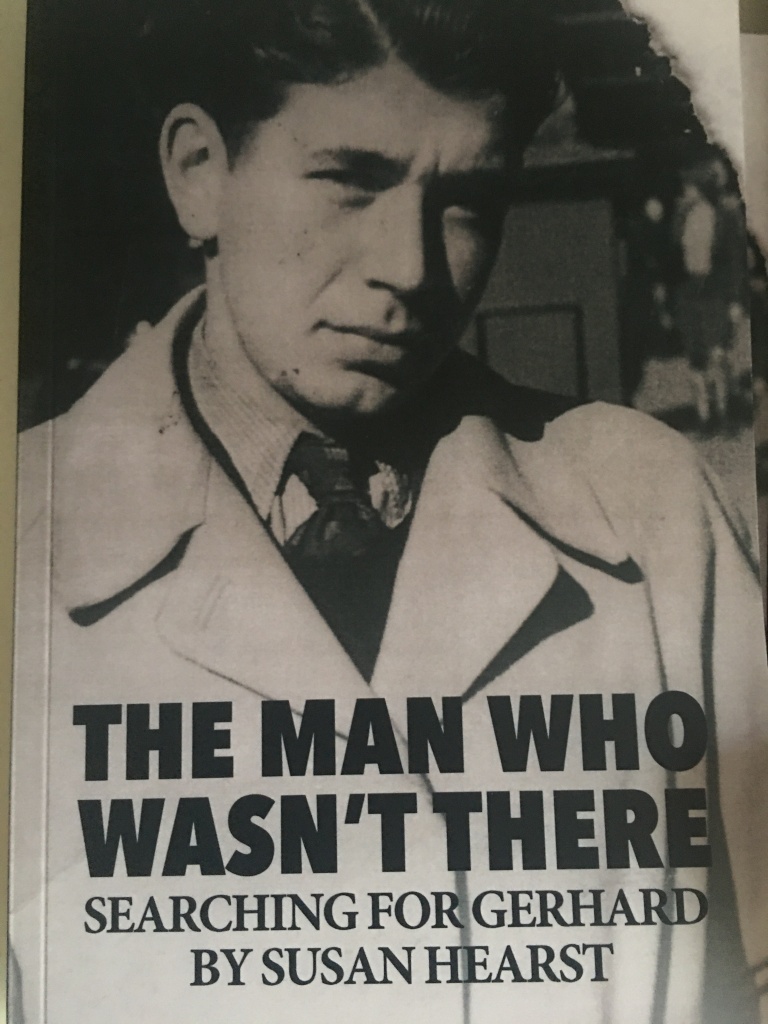

The Man who Wasn’t There – Searching for Gerhard

By Susan Hearst, nee Friedlander

Melbourne

Beth Weizmann, 308 Hawthorn Rd, Caulfield. Sunday 01 December 2.30pm

To buy: phone Lamm Jewish Library +61 3 92725611 or email info@ljla.org.au.

I acknowledge the Aboriginal custodians of the land on which we meet, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin alliance, and pay my respects to their elders past present and emerging.

Remembering is a personal and a political act – a stand in that flow of history that otherwise dissolves the past from under us. In oral cultures history become myth and is repeated through the generations, in rituals of story-telling. As people of the book we are drawn to writing the stories, perhaps no less ritualised or myth-repeating.

The aim of the Holocaust, though such a tragedy cannot be so sanctified with any sense of a rational mind at work, was to remove the telling of the long narrative of the Jewish people, by removing the people. The first action by the Nazis involved burning books, then burning synagogues and homes and shops, and then burning people. The writing of a book about our history represents a step forward into the face of those who burnt everything precious. The palm rises into the hoard bearing down on us, tripping up and hurling aside the hooligans of eradication, reinscribing on the palimpsest scraped free, our record of lives lost but now no longer forgotten. As Susan and I had chiselled into our grandmother’s grave in Sydney “As we live, she lives”.

Family histories are exemplary ways to communicate the long story of love and caring and human frailties and strengths, stretching back into an infinite regression. They also foreground through their telling those values that are to be communicated into the future, to children, grandchildren and onwards, to be read not just now but again and anew. So Susan has done not only her own good work, but good work for many others of us, and many others of her own.

This book is partly about heart-break, about the way in which the Holocaust rolls on through the decades, catching and shaking the lives of survivors and their children. It is also about discovery, and quite literally putting the pieces back together again, out there in the narrative, inside in the heart.

When Susan asked me to launch her memoir and investigation into her missing father, I was honoured but worried. When you start opening the discarded baggage of other peoples’ lives, you can disgorge stuff that has no resolution. And so with this set of stories, and nearly all of her own doing, though with a little help from her friends.

Susan and I have been close forever, from the time we used to eat mangos in the bath when kids in the Blue Mountains, or cower from the anger of adults when we had done something quite naughty as we played in the house in Bentleigh. I vaguely remember her in the dark serge of St Gabriel’s school, just around the corner from our place in Bondi, chosen for her by a single mum who had to work.

The stories of Maria and my parents and our mutual grandmother were the stuff of our childhoods, great escapes and dumb silences. In her wonderful analysis, The Silence: how tragedy shapes talk, my old friend the late Ruth Wajnryb takes us on a journey to disinter the stories from the many silences with which we are surrounded. For Susan these silences were palpable, both that kept by her mother, and those left like a relentless wake by her father. As Susan says of her mother and her one great passion, a man who appears suddenly, momentarily yet warmly in these pages, that when she could tell she wouldn’t tell, and when she would’ve told, she could no longer tell. Everything can be in the telling.

The book picks out the pieces of Susan’s family – firstly the survivors who escaped from Lodz through Vilnius to Japan. Some of that narrative lurks in the memoir by our uncle Marcel Weyland, The Boy on the Tricycle. Some I have referenced in a series of academic articles on Shanghai and the Jews of China, also an exhibition at the Sydney Jewish Museum in 2001. Some is in the interviews recorded for the Shoah Foundation by the late Maria Kamm, Susan’s mother, many years ago. Yet Susan’s story only gestures to how my side of the family, my parents Hala and Bolek, and our indominable grandmother, Babcia Weyland, shaped what would happen to her. Perhaps we were not always great for her, however well-meaning we might have been. Gerhard and Maria were a young married couple when my tribe arrived from Shanghai and moved in with them at Kings Cross in 1946. The marriage didn’t last that much longer. Susan alludes to a dynamic that shifted their love affair of wartime to the reality of the postwar recovery, when Gerhardt left and effectively disappeared. Everyone else knew more about him than she was ever allowed to know. Except me, I knew nothing.

Searching for fathers lost through the Holocaust has become an oft-repeated but always demanding laneway in history. So often it was the mothers who shielded the children, arranged their escapes, led them to safety. The fathers were taken earlier, found it harder to hide, went on their own adventures. So it is for Susan’s search for Gerhard, George, the man who introduced my recently arrived father in post-war Sydney to the six o’clock swill, where he would drink ten icy schooners in a row thinking he would die of a frozen throat. George who convinced my father to go on a road trip into southern Queensland where he noted that the water in Roma, tasted oily, missing the chance to become an oil magnate. And George who one day was no longer there.

Why had Gerhard deserted her as a baby, this German refugee, with a family lost in Europe, hanging out with a young Polish woman? Did he love her- either Maria or Susan? What did he know about his own family? Why had he cut off all contact? In bursts, Gerhard emerges like a body sculpted from marble, cool, distant but increasingly distinct as Susan discovers elsewhere many of the answers to questions she wanted him to answer. But of course not the one that matters.

Intention and serendipity intertwine, blocked passageways open out, people appear out of unformed landscapes with fragments of the story. Susan puts them together like a jigsaw, moving the pieces around as her writing tests propositions of possibilities and then tightens the logic from the evidence she can nail down.

We skip from Australia, to China, to Poland, to Germany, to Norway, to Palestine, to Israel, to north and south America, to Chile and on. Along the way there are many stumblestones, not just the ones sunk into the cobbled streets of Berlin or Vienna to remind the passers-by of their stolen Jews, but those created by history in the soul.

We meet Susan at the beginning of the book as an orphan with an unknown father and nothing more, isolated on the edge of the world. By the end, the families in which Gerhardt played a part have dimensions in time and space, and Susan is wrapped in an extended network of caring and memories across five continents – I await to hear the story from America of the distant cousins who survived through a Shanghai escape: where my own parents found refuge.

Throughout the book there is the figure of Gary, from the first call from my parent’s home to a momentarily rediscovered Gerhardt 44 years ago, to the guide he offered to Susan through his own tragic landscape of Austria and Byelorussia. He knew there was a “piece missing” for Susan that had to be found for their family together to be made whole.

In publishing this book Makor extends the Loti and Victor Smorgon Community Archive, which comprises all the books in the Write Your Story program, adding to its already renowned and impressive portfolio a unique “take” on the meaning of survival. The Makor/ Smorgon archive is the largest publisher of Holocaust memoir in English in the world, and I wish to recognise the contribution they make to the reinvigoration of memory, and the survival of culture.

This book is a good read, moving, insightful, sharp, curious, not unlike its author.

I have great pleasure in launching this book, The man who wasn’t there: In search of Susan…

Excellent, covers a lot of angles. Congratulations to the author and to Andrew

Dear Sir,

I googled my late fathers name, Gerhard George Friedlander, as I knew very little about his past. Believe me I was quite surprised to find a picture of my father as a young man looking back at me from a cover of a book.

I would be interested if you could contact me at my email below so I could discuss some things.

Kindly yours