May 1 2016 Bondi, NSW JIFF: talk to the Jewish International Film Festival audience for Courage to Care

I first wrote something about Sugihara when I was 9, in a primary school essay. I cannot remember when I didn’t know about my parents’ escape from Lodz in the first week of the Nazi invasion, and later the tragic fate of my father’s parents, murdered in the Lodz ghetto and at Chelmno, and the marvellous survival of my aunt and cousins protected in a forest sanctuary by Poles, and others hidden by nuns. They were stories told to a child, full of serendipity, of choices made, of hunches played, of disasters just avoided, or those horrendously experienced. Many of these will be revealed in detail in the autobiography of my uncle Marcel Weyland, a Sugihara survivor, which I am honoured to launch at the Polish consulate on May 12.

My father had told me about standing in a long line of anxious Polish Jews outside the Japanese consulate in Kaunas in the hot sun in August 1940. He and Michal Weyland my mother’s stepfather, had left the rest of the family in Vilnius and travelled the few hundred kilometres to the then capital of Lithuania. Sugihara had started issuing the permits soon after the Soviets had presented Lithuania with an ultimatum in June to accept their sovereignty. For my father it was one day before the final Soviet annexation of Lithuania.

The men wanted the Japanese permits about which they had heard, that would let their families transit Japan for somewhere else. Already when they arrived the Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara had issued over 800 permits. During the next week that number would grow by many hundreds more until the list that records these names stopped in late August at over 2100.

My parents were on the run from the Nazi occupation of Lodz in what had been Poland. By the time they left Lithuania in February 1941 under the intensifying threat of having to take Soviet citizenship, they had secured the second crucial piece of their puzzle. While they’d never met, Jan Zwartendijk and Sugihara worked in tandem.

Zwartendijk, a Dutch businessman, had taken on the role of consul for the Netherlands, a country already invaded by the Nazis in May: he wouldn’t be consul very long and he destroyed all the relevant documents before returning to Holland at the time Sugihara was expelled from the Lithuanian SSR. Zwartendijk devised a ruse, stating that no visa was required for entry to the Dutch colonies in the West Indies. One of the refugees who was Dutch had approached him for help: the news of his help for her and her immediate family spread rapidly.

Zwartendijk also knew that entry to Curacao was at the discretion of the Governor, and he rarely if ever gave permission. Even so this is what Sugihara needed to be able to legitimately issue the transit passes, a place to which the visa holders could transit. With this fictitious end point he could meet Tokyo’s insistence that the transit pass holders had somewhere to go, that they wouldn’t stay in Japan, and would pay for themselves. In Kobe the local Jewish community started producing guarantees of support for the refugees from Lithuania who soon would be arriving.

Sugihara was a magician. He was also a Japanese intelligence officer, running a string of Polish agents in occupied Poland, helping Polish officers and their families escape, and reporting on the Nazis preparations for the invasion of the USSR: once that happened Japan could move south.

There are many stories about how he pulled the rabbit out of the hat for the refugees, not all Poles, not all Jews, and at whose insistence. When I met his eldest son Hiroki in Los Angeles in 2000 (he died of cancer the following year) he recalled as he had for many interviewers, that he had played in the garden while watching that long line of Jews and how he had asked his father to please save them. On the wall of the consulate today, which is now the Kaunas Sugihara museum, there is a photograph of my mother, elegantly attired arm in arm with two friends, walking up the broad main street of Vilna in what must have been the summer of 1940. It would have been about the time Sugihara started issuing his permits, and the same time the Australian government was instructing its High Commission in London not to give transit permits to Polish Jews heading for Shanghai – they were “undesirable types”.

At any moment in Lithuania the NKVD might intervene or Moscow’s policy might change, especially once the family had the papers, and the Soviets were fully in charge. My father was an accountant in Poland and in Vilnius he was recruited by the Soviet occupation forces as part of the Sovietisation of private property program. I have always imagined it a cruel and bitter winter, a chiaroscuro water colour of light ebbing into darkness. My father was attached to a bakery under the impossible new economy of Stalinist state directives with production targets but no raw materials: it was dominated by central planning, subverted by the local Lithuanian baker and his family whose family livelihood had been stolen, who hated the Soviets as both Russians and communists, the Jews for being their agents (my father as a Pole and a Jew pressed two buttons, but he was outshone by the project Commissar who was Russian, Jewish, and Yiddish speaking and a communist), and reduced to chaos by the failure of the economy.

Prior to departure, when the refugees had their tickets to Moscow and Vladivostok, and their identity papers issued by the British consulate, they were called in the dead of night for the dreaded NKVD interview. On the outcome of this would hang their lives. The NKVD officer was also Jewish; while he insisted on only speaking and hearing Russian, he could overhear anyone speaking Yiddish. They shuffled up the stairs slowly edging towards their destiny. When he got there my father was offered, as had been the others, the opportunity for Soviet citizenship. Nervously he declined, perhaps making a slightly more courageous offering than he needed: “I cannot accept your invitation comrade, he said in fluent Russian, as I can have no future in the USSR. Why, asked the commissar, might that be as you have been working for the Sovietisation of private property? Well, my father said, I am not skilled in what you need, for in my past life I was a debt collector.” He was waved on, and so in the midst of a freezing February 1941 they were among the last of the Polish Jews to manage the escape. By March the Soviets closed the door, and despite pleas thousands more, some with visas, were trapped behind. In four months the Soviets would be gone, the Nazis in their place, and the majority of the 10,000 Polish Jews who had escaped to Vilna in 1939 had perished.

Not everyone who got them trusted Sugihara’s visas. Some managed to go elsewhere, often to Palestine via the USSR and Turkey. Others went back to find their families in Poland, and perished. But many took the risk, including the Mir Yeshiva, my parents and my mother’s immediate family, and a journalist Josef Kamieniecki who would later marry my aunt in Australia. The family path was through Moscow across the USSR to Vladivostok, then by boat to Tsuruga and on to Kobe. In Kobe they received support from JewCom, the American Jewish Joint Distribution committee, and the Polish government in exile through its Ambassador Tadeusz Romer, who later was expelled to Shanghai where he continued his support work. I discovered only a few weeks ago that Romer’s welfare fixer was Richard Krygier, who managed to get from Kobe to Australia before Pearl Harbour. His son Martin has become a distinguished professor of law.

How many people did Sugihara save directly – it’s a guess? He issued more than 2000 permits, but not all are recorded. Many covered whole families (some rabbinical students travelled six to a permit as a “family”) in our case two permits covered six people. Most of the holders were single men. According to JewCom in Kobe, 4600 people passed through Japan from July 1940 to November 1941. About half were German Jews, mostly not Sugihara holders; about half (2063) were Polish Jews, almost all of who were Sugihara holders. Of the Poles 500 went to the US, 190 to Canada, 250 to Palestine, 80 to Australia and 30 to New Zealand. About 110 got to South America, none to Curacao. Fifteen headed for northern China, one of who was my uncle Josef. 860 were in Shanghai as of November – together with 200 Germans from Kobe (there were 18,000 other Germans already there).

While the family hoped to keep going to somewhere else, they had Canada in mind, in September 1941 they were hustled by the Japanese onto the last ship from Kobe to Shanghai. Once there my aunt managed to get the last berth on a Dutch ship to Australia. The rest of the family stayed in Shanghai until 1946. Michal died of cancer in 1942. The remaining four survived, along with the man who would be my godfather Aleksander Fajgenbaum, a hero of the anti-Soviet war of 1921 and the battle of Warsaw, a leader of the community and a bridge between Jewish and Christian Poles in Shanghai.

In Shanghai five of the Sugihara survivors gave their lives defending their right to be Polish citizens, rather than the stateless persons the Japanese had decided they were. Sugihara, a great friend of the Poles, would have been saddened by their tragic end, as he was for all his life an opponent of Japanese militarism.

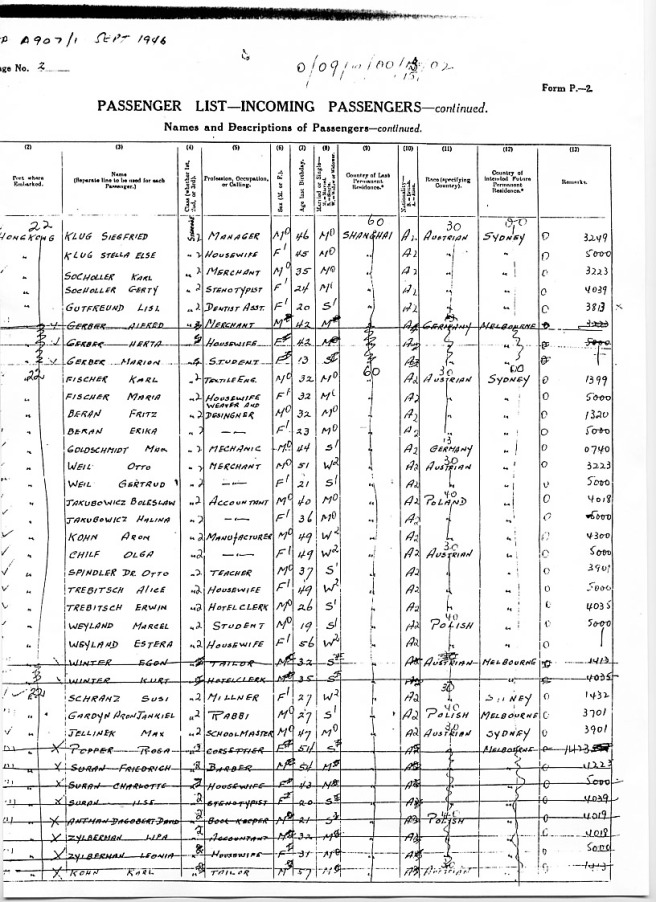

In 1946 Maria and her then husband Gerhard Friedlander sponsored the four remaining family members from Shanghai, and they entered Australia through a brief window that the government opened; soon it would be closed in another round of Australian post-war anti-Semitism. Josef arrived in January 1947.

And the rest is history.

Or not quite: the magicians – Sugihara, Zwartendijk, and Romer – between them saved many thousands of people who have created many thousands more. In my mob the second generation comprised nine cousins; in the third generation there are twenty six cousins; and the fourtth generation is already sprouting, with a few outliers in the fifth. There has to be sixty or so of us if not more. A healthy mix we are of cultures, religions, and races.

In Japan Sugihara’s home-town of Yaotsu is applying for UNESCO world heritage status for copies of the Sugihara visas it has collected and for what they represent. One of their prize items belongs to Josef Kamieniecki, father of Prof Michael Kamm and Robert Kamm, and grandfather of Thomas and Rebecca, whose widow is Marylka Kamm nee Weyland, mother of Michael, Robert and Susan, sister of Marcel and grandmother as well of Antony, Jeremy and Elise. Josef was one of fourteen who went to Harbin from Kobe, and then south in 1942 to Shanghai.

Marcel fathered five children with Phillipa – Marcus, Antonia, Michaela, Julia and Lucian.

Susan is currently in Berlin, tracking down what happened to Gerhard’s family, Berliners who were seized by the Nazis, sent to Latvia, and murdered there.

They all live in our memory. Long life. L’Chaim. Arigato Sugihara-san.

I am ashamed of Australia’s pusillanimous attitude in the circumstances.

I’m glad that Susan had sent me your report. Last week Susan had the possibility to enter the last flat of her grandparents Josef and Gertrud Friedlander in Berlin. From there they had been deported to Riga and executed in January 1942. Their to sons emigrated in time: Max to Palestine and Gerhard – Susan’s father – to Australia.

Thank you Norbert — usan has been keeping me up to date with her visit. Your work for her has been wonderful. an extraordinary series of sad, poignant, horrific, uplifting revelations. i am looking forward to the english version of the diary.