Andrew Jakubowicz Launch 12 May 2016 at the Polish Consulate Woollahra Sydney.

While I have been in Marcel’s consciousness some few years more than he has been in mine, I am honoured that he has asked me, the nephew, to help launch this memory of a life well lived.

From my earliest memories he was part of my family world, with the trips from Bondi to the rambling mansion at Mosman, and my getting to know the line of cousins and that mysterious string of Irish relatives brought into our family through his marriage with Philippa.

His life has trailed the history of the modern world, starting from the calm comfort of a bourgeois home in Lodz, Poland, and being completed but by no means finished now in the other bookend in Sydney, Australia, his ever spreading offsprings’ offspring melding with the children of other immigrants from all over the world.

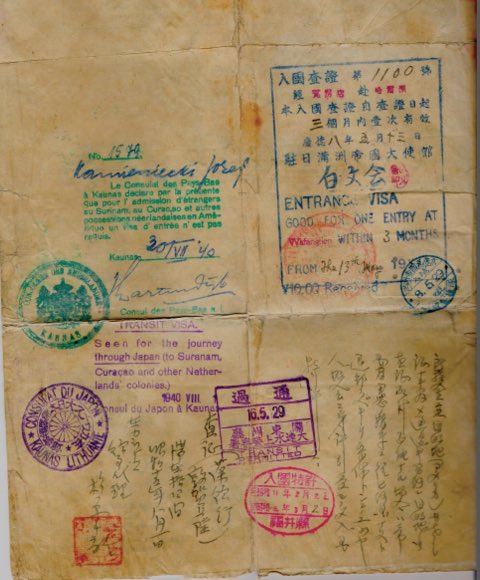

I have seen his memoir emerge at a steady pace, and watched how memory and contemporary prospect intertwine and feed on each other. In June last year some of his memoir was shared via video in progress with family, friends and interested observers at a ceremony I attended in the Synagogue in Warsaw. Then three months later, the invitation to him I had been handed there and trusted to deliver by Japanese officials, was realised as he was guest of honour at a ceremony in Kaunas Lithuania to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the role that Chiune Sugihara had played in the survival of our family. While Marcel was in Kaunas, Mara and I were in Shanghai watching a musical “The Jews of Shanghai” performed to celebrate the end of the war against Japan, which permitted him to take the final voyage to freedom in Australia.

This is very much Marcel’s night, and it represents another milestone in an extraordinary career that he has developed as a bridge between the many societies where his life paused in its trajectory. Born in Poland, saved firstly from the Holocaust in Lithuania by British officials representing Poland, and by a Dutch and Japanese official who was running Polish secret agents, and then a Soviet officer, then permitted to escape across the USSR, settled for a time in Kobe, Japan, then shifted unceremoniously to Shanghai, where suddenly all forward movement halted, Marcel arrived with my parents and his mother in Sydney in September 1946 where his sister Maria, greeted him. This sputtering but magical journey is only one part of a tremendous life, part luck, part courage, part adventurous imagination.

There were many moments of extraordinary luck and serendipity, which he records with a wonderfully wry style in this book. We were discussing one of those – why and how did he get to Shanghai, last year. I wanted to know more and after the trip to Shanghai and a turn in the archives there I had even more questions. There are at least three heroes in Marcel’s story – Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul in Kaunas; Jan Zwartendijk, the inventive Dutch honorary consul in the same city; and the Polish Ambassador to Japan Tadeusz Romer, who was moved from Tokyo to Shanghai about the same time Marcel was shipped from Kobe to that same city.

Marcel and the family were on the last boat to Shanghai. Up until July 1941 the expectation of most of the 2000 Polish Jews who had used Sugihara and Zwartendijk papers to get to Japan, was that they would get out to North America, South America, Australia or Palestine. Maria had already secured a link to a refugee accepted by Canada, later known as Stefan Golston, serendipitously as we now know also a translator of Polish poetry. However at the end of July all shipping out of Japan to the west was halted, as was the flow of money to support the refugees from the USA. The civil authorities in Kobe decided that the final 1000 Poles had to leave, and they sent three ships to Shanghai. Our family remained in Kobe, maybe because they still hoped to get to Canada, maybe because unlike many others they were not destitute as my father worked for the local JewCom.

In Shanghai the Japanese military authorities were very unwelcoming; in their view the Polish Jews were undesirable and would not be allowed to land in Hongkew where the Jewish community had housing. The Vichy French banned entry to the French Concession. The Jewish community confronted the Shanghai Municipal Council, an international body run by British officials, and demanded they help, or they would cable Kobe and tell the refugees not to leave.

The confrontation continued – the community had housing where there was no entry allowed, and where entry was allowed they had no housing. When the third boat arrived at the end of August the passengers disembarked on the Bund and were first housed in the Museum Road synagogue.

The following day the community reported the synagogue as over crowded to the Council, demanding it find alternative accommodation. This ruse did not work but soon after the arrivals were allowed into some of the housing in Hongkew; the rabbinical students (about 300) stayed in the synagogue, and the others moved to the Jewish club in the French Concession. Marcel and our family arrived on a fourth ship that left Kobe on September 15. They were then moved to a house belonging to the Catholic church in the French Concession – we visited it again last year, preserved by the Shanghai city across the road from the Shanghai Hilton.

As the memoir notes, Marcel then tracked off to find a school, repeating an adventure from Kobe, and by October he was at the Shanghai Jewish School. Michal their father urged Maria, who had the Canadian visa, to take the last berth on a Dutch boat heading for Australia, entry arranged through Romer’s good offices. It would turn out to be the last ship out, and their expectation that Maria would do the necessary to help them also leave did not occur until June 1946.

In 1943 the remaining family members were ordered to move into Hongkew (The Designated Area), where they lived in a house in Dalny Road. Mara and I saw it being demolished in 2000 for the new metro station near the Jewish Refugee Museum.

I want to make short mention here of five of the Polish Jews whose lives ended in Japanese custody, when they protested the move to the Ghetto. They tried to assert that they were Polish citizens not stateless refugees: to no avail. The five had all received Sugihara visas in Lithuania in 1940; they had travelled across the USSR and found refuge in Kobe in 1941; they had been shipped to Shanghai in late 1941, two on the last ship in September. In a very real sense they were the Jews who martyred themselves for the Polish cause; their names were Josef Altminc (from Warsaw, 45 yo, JDC Vilna list 64, Sugihara list 157, Polish consulate list 1340); Berysz Abramowicz (Sugihara list 1376, Polish consulate list 1054); Aleksander Halperson (Sugihara list 370, Polish consulate list 1200); Gersz Praskier (Sugihara list 1048, Polish consulate list 1131); and Teodor Finkelstein (Sugihara 1680).

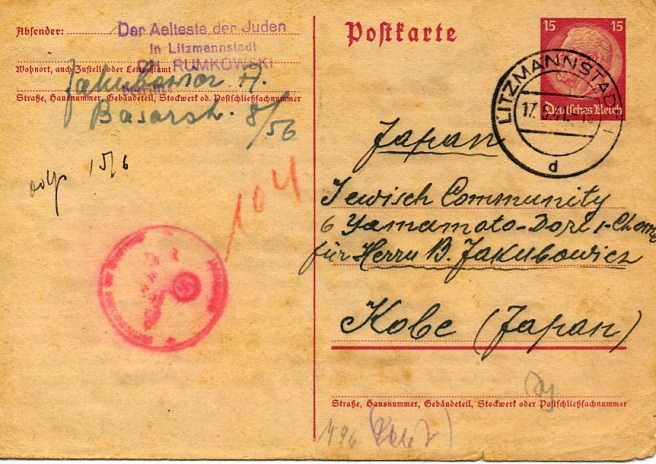

In September 1946 Marcel and his mother, with my parents, arrived by ship from Hong Kong on the SS Yochow, at Woolloomooloo. Michal had died of cancer in Shanghai in 1942. My father’s parents had perished in 1942 in the Litzmannstadt ghetto (Lodz) and at Kulmhof death camp (Chelmno) in Poland.

With great emotion and heartfelt thanks for his life and the magic that allowed him to live it, I declare the memoir of the boy on the tricycle launched, and ask Phillip Hinton to read to us from its wonderful text.