The Multicultural Framework Review was launched on Friday evening, June 2. It raises the question, is multicultural policy something that should be “for all Australians” as was declared in 1982, (http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/doc/auscouncilpop_1.pdf) or just to ensure, as the announcement of the Review put it in February “no one is left behind, and everyone feels that they truly belong”( https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-publications/submissions-and-discussion-papers/multicultural-framework-review ) ? The Albanese government’s Multicultural Framework Review, shepherded by Immigration and Multicultural Minister Andrew Giles, has possibly been set the more modest goal, despite a recognition by one of its panelists, Melbourne lawyer Nyadol Nyuon, that the original multicultural policy developed fifty years ago by the ALP’s Immigration Minister Al Grassby “had a far-sighted vision of what this country could become”.

The government has identified the triggers for the review – “nine shameful years of fear-mongering and division… failures to translate vital health information during the pandemic, and government support and grant programs inaccessible to emerging migrant groups”.

The revised Terms of Reference (https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about-us/our-portfolios/multicultural-affairs/multicultural-framework-review note that the Review is designed to help ensure a government that works for a multicultural Australia. While it eschews a human rights perspective it does identify discrimination, systemic barriers and gender intersectionality.

While the ALP won the 2022 election with seats gained by “multicultural Australian” candidates, it also lost the most multicultural electorate of Fowler to a local candidate Dai Le who campaigned successfully against the marginalisation and abandonment of those multicultural voters during the pandemic and the parachuting in of a White candidate. With the opening up of borders and the resurgence of the issues raised by immigration, multicultural policy is once more critical to wider social well-being.

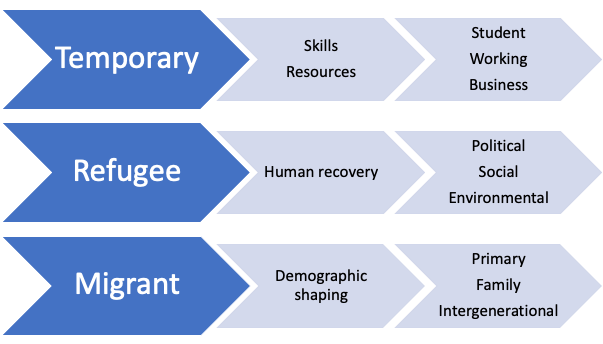

Over the past decade perhaps the biggest sleeper issue has been the massive increase in extremely insecure temporary migration, sometimes used as a subterranean route to permanent settlement. However public policy has assumed that “temporary” means “not requiring support”, so the level of services – from housing to transport to education to employment protection to health – have not factored in these supposedly temporary but very real residents. They were the ones most abandoned during the pandemic, when they were told simply to “go home” or to survive on the streets. Now they’re coming back.

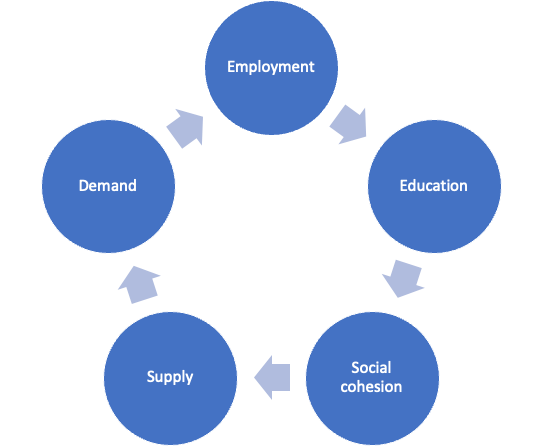

There are three broadly intertwining spheres of policy that require major refreshing – multicultural policy (including language policy, intercultural relations, cultural recognition, employment policy), settlement policy (focused on new arrivals both refugees and others, including trauma recovery), and community relations (covering discrimination, anti-racism, diaspora continuity and social integration, and the all-important dimension of settler-Indigenous relations). These are serious dimensions of governance that have been left to decay for the past generation, including during the ALP inter-regnum from 2007 to 2013.

Multicultural policy reached its apogee in 1989, with the Hawke government’s National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia. It began to decline under PM Keating who did not implement key elements of the policy. It was picked apart by PM Howard for whom multiculturalism was an anathema. Most of the damage done by Howard has been let lie.

In order to see what was lost and what now might be worth reclaiming, we can identify the targets of the Howard attack. While driven by the 1984 Blainey critique of Asian immigration and the 1988 Fitzgerald review of immigration and multiculturalism (Fitzgerald was a fervid but not successful opponent of the multicultural agenda under Hawke), the accelerator for the bonfire came from the impact of Pauline Hanson on the conservative parties in 1996.

Howard’s most critical move was the effective abolition of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, the co-ordinating policy section in Prime Minister and Cabinet. This was closely followed by the closure of the empirically-focussed Bureau for Immigration Multicultural and Population Research, condemning policy for the next generation to hyperbole based on prejudice, ignorance and ideology. In the wash the National Language Policy also dissolved, reducing the bilingual capacity of the country for decades to come. Keating had already given up on any attempt to introduce a Multicultural Act as in Canada, focusing instead on Access and Equity in government, while deeding the country the fairly toothless Racial Hatred amendments to the Race Discrimination Act (so called 18C).

How open is the the power hierarchy in Australia to non-European Australians? Addressing this issue remains a major challenge – best seen in the make-up of the High Court, the members of the Board of the ABC, the Vice Chancellors of the Universities, and the Boards of the major ASX companies (https://apo.org.au/node/140206).

The Review will consider the Commonwealth’s activities and will be able to make recommendations on legislation, policy settings, community relations, and government services including state and local. Importantly it will consider the role of the Commonwealth as an employer, as recent studies have pointed to the under-representation of culturally and linguistically diverse groups in government at both Commonwealth and state levels. Better put, well-paid White monoglots run the services in the broad, and non-White multiglots deliver them – in greater proportions the lower the pay levels.

Unfortunately the Review is not asked to take notice of the poor state of Australia’s data on diversity and its appalling consequences, most significantly in the pandemic https://johnmenadue.com/a-tale-of-two-cities-same-pandemic/ and https://theconversation.com/we-need-to-collect-ethnicity-data-during-covid-testing-if-were-to-get-on-top-of-sydneys-outbreak-164783)but also today in terms of mortality from COVID, now particularly destructive among older “multicultural Australians”. Neither is it asked to consider how to rebuild the depleted state of Australian research in the area, a central recommendation (at page 123) of the last ALP-led parliamentary committee review of multicultural policies in 2013(https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=mig/multiculturalism/report.htm) (and totally rejected by the incoming Abbott government).

The Panel chair Dr Bulent Hass Dellal, is well-blooded in these debates. He has held to a sensible course as a government advisor throughout the Abbott/Turnbull/Morrison period, and also has the confidence of the new government. Interestingly Giles has chosen two Victorians and a Queenslander for his team, leaving NSW to two people on the Reference group, with someone from Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia.

There are no First Nations people, or people with mixed First Nations and non-Anglo heritage, though they will be invited to contribute their perspectives. As the Voice debate has shown, multicultural Australia wants to engage with the Indigenous peoples (https://theconversation.com/will-multicultural-australians-support-the-voice-the-success-of-the-referendum-may-hinge-on-it-199304) .

The government has appointed no academic researchers to either the panel or the reference group, though Queensland’s Christine Castley is a former Deputy Director General of Premier and Cabinet, a Board member of the University of Queensland Institute for Social Science Research, and currently CEO of Multicultural Australia, a service delivery conglomerate heavily funded by the government.

From the perspective of Australia’s knowledge communities (identified in the Review as experts to be consulted) with an interest in cultural and linguistic diversity, and what the Diversity Council of Australia now refers to as “racialised marginalisation”, the commencement of the Review is disappointing. The absence of issues about data (which are currently focussing the minds of the Australian Bureau of Statistics in preparation for the next Census (https://consult.abs.gov.au/census/2026-census-topic-consultation/) ), the complete exclusion of the research structure issues, and the small passageway left open for consideration of an Australian Multicultural Act (one is already on the Senate table from the Greens dating back to 2017) and agency associated with the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, are not comforting signs of recognition of the scope that needs to be addressed.

Most unfortunately this Review is being sponsored by a junior Home Affairs Minister. In previous times multicultural policy was thought important enough to have the support and imprimatur of the Prime Minister – be it Malcolm Fraser or Bob Hawke. Not so now.