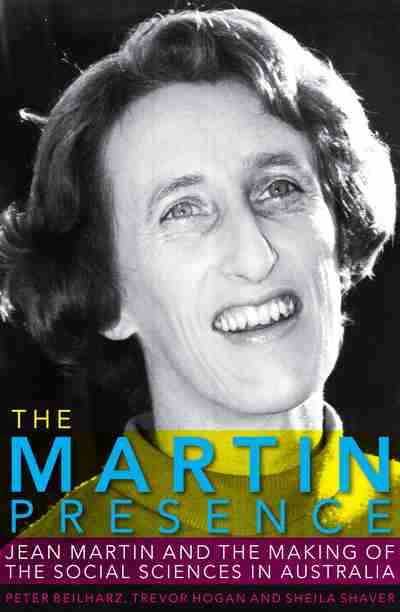

The Martin Presence: Jean Martin and the Making of the Social Sciences in Australia

Paperback | Jun 2015 | UNSW Press | 9781742232164 | 304pp | 234x153mm | Stocked item (plenty) | GEN | AUD$39.99, NZD$47.99

Digital (EPUB) | Jun 2015 | UNSW Press | Stocked item | GEN

Digital (EPUB) | Jun 2015 | UNSW Press | Stocked item | GEN

Launched by Andrew Jakubowicz at Gleebooks Sydney 18 June 2015

- I recognise the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. Great honour to be asked to launch the book by . On reflection it may be that there are few enough of us around that knew her and still have held onto the memory. I am reminded of my own somewhat inglorious earlier years by the authors’ account of internal struggles over the control of the sociology journal 45 years ago. Terrifyingly, it was just a moment ago.

- A week ago in Warsaw in the palace of culture I was engaged with Polish scholars on the future of multiculturalism. Next was two days of refugee survival conferencing during and after WW2. The qualities of the dialogue in both cases had many Martinesque qualities.

- In reflecting on The Martin Presence I am instructed by Martin’s 1971 SAANZ Presidential address when she chose Camelot as her motif, and proposed three central tasks for sociology. She would undertake an archaeology of ideas (a pre-Foucauldian adventure); she would document the reality of the world in which it occurred; and she would problematize the relationship between sociology and the state.

- This book by Peter Beilharz Trevor Hogan and Shelia Shaver about Jean Craig/Martin, draws back into the imagination those extraordinary years of the birth of Sociology in Australia, as the new waves of social philosophy that brought feminism, European Marxism and activist social science crashed thunderously against the cliffs of an earlier more measured, self assured, masculinist and developmentalist Australia.

- Jean Craig came from that particular layer of the Australian elite that found its roots in the professional engineering class of Scotland, which then spread out across the empire to build its bridges, railways, and cultural institutions. These were the people who would produce the grand nationalists and thinkers such as Geoffrey Blainey and Malcolm Fraser, steered by austere moral compasses. It was of them the Protestant ethic in its British form was devised.

- Craig was “fortunate” to find one of the spaces for women of intellect that opened up during WW2, as the academicians marched off to War. These spaces would tighten shut on the return of the men, and Jean would face the next wave of masculinism as she embodied the second wave of feminism. Inculcated in the disciplines of anthropological fieldwork at Sydney university, she would later immerse herself in the sociological foundry of Chicago, and return a dynamic synthesis of Europe, Britain and America.

- My career began as Jean’s was reaching its crescendo: recruited from Henry Mayer’s Government kindergarten by Sol Encel, I first encountered Jean in two guises. As a young PhD student I was caught up in the Henderson poverty inquiry and with Berry Buckley began researching the impact of the legal system on the social inequality of immigrants under the tutelage of Ron Sackville. Jean was already well established as a defining thinker in the field of immigrant and refugee studies, pointing with a theoretical armoury drawn from Durkheim and Weber, at the processes through which Australian society was distancing immigrants from real participation in the constitution of the social order. I was also a generation younger and joined the revolt of the young at the SAANZ conference of 1971 when Frank Jones, the young but already conservative symbol of “collaborationist” sociology was rolled by Lois Bryson as editor of the journal. Jean was saddened and I think shaken by the tensions that separated the small sociological community, along slivers of ideology rather than patterns of scientific discourse.

- In terms of method Jean was eclectic, though she had ingested the Weberian maxim of commitment of the heart and isolation of the mind. She would choose her issues because of what drew her emotionally and to some extent politically, while seeking to ensure her methodology was pristine and uncontaminated. The Camelot speech allowed her to worry at this issue, especially as her desire to use sociology for human betterment was placed in critical perspective by the revelations about project Camelot, the US attempt to use social science to predict and repulse social revolutions in Latin America and in Asia. In her own small way she would be laid low in her final project by exactly the crass politicisation of research she had hoped would not intrude into Australian intellectual and policy life.

- Jean’ s work on immigrant settlement was empirically rooted and theoretically informed. She gained deep insight into the experiences of the post war immigrants especially the Eastern Europeans; her colleague Jerzy Zubrzycki she was able to understand as both a sociologist and an immigrant and a sort of intellectual DP, and his exploitation of her (and perhaps her of him) provided a productive channel into government for a while. Her ideas on ethnicity were influenced by Weber’s concept of ethnic groups as status groups, and she was beginning to understand Foucauldian ideas of power. She thought Marxist ideas to be unhelpful, though she saw economic inequality and its corrosive effects as problems that could be addressed within capitalism to the greaater benefit of all.

- Peter Wilenski, Gough Whitlam’s PPC and then the short-lived head of Labour and Immigration, wanted Jean to track the survival of the Vietnamese refugees arriving in 1975. Fraser’s election put an end to that, and soon Jean was dead, taken far too young by a cancer that corroded her final years.

- The Migrant Presence, a sociological study that was in part a report to a government committee, that would be fundamental ultimately to the institutionalisation of multiculturalism, remains Jean’s greatest legacy. That single book, with its insistence on systematic theorisation, empirical evidence, and logical evidence based policy development, remains I would suggest a pivotal document in Australian social history. Before it, immigrant marginalisation was omnipresent; after it Australia could no longer avoid the centrality of the migrant presence. Ironically after destroying her final work on the Vietnamese (completed years later by her student Frank Lewins) Malcolm Fraser’s legacy of multiculturalism would depend in its skeleton on Jean’s imagination, sophistication, and sensitivity to the intricate patterns of relations that allow culturally diverse societies to prosper. Fraser’s reputation among Vietnamese Australians would depend on policies that Jean had prefigured, but the evidence for which Fraser himself had sidelined.

- The authors argue that multiculturalism and immigration no longer have bipartisan support – on this I would beg to differ, suggesting that the particular skew in the Australian economy – we much prefer to import our intellectual capital rather than invest in it here at a serious level – will continue. Indeed it was under Martin’s last broker, Wilenski – that immigration tanked. Since the vapid bounce around the population bubble debate of five years ago, all continues and multiculturalism is now being spruiked as the base for opposing gay marriage. The fear of Indo Chinese that Martin saw in her last years has morphed into fear of Muslims.

- The authors have been meticulous in their collection of evidence, in the writing of this intellectual biography, and through it, revealing the dynamic between ideas, social practice and political power. My last memory of Jean comes of an evening spent with her and Allan in the Kew house, slightly too much red wine and a vigorous argument over how to “read” Australia – and where multiculturalism might go. I remember leaving into a warm summer night, and hitching a ride with a bunch of hoons in a hot Holden into the city. Soon I was on my overland trek into Asia, and by the time I was back Jean was dying: I never saw her again, though my return from Bradford to establish the centre for multicultural studies at the University of Wollongong might have caused a slight knowing smile to touch her lips had she been aware. Her opus became both a guide and a provocation to our small cell of Illawarra multicultural Marxists.

- As one of the many Poles whose lives crossed hers, her beloved displaced people whose shenanigans she followed and whose dynamics she examined, and that swollen pod of sociologists like Zubrzycki, Encel, Pakulski, Jamrozik, and Jakubowicz whom she influenced, it gives me great pleasure to declare this book well launched. I commend it to those for whom Jean was a comrade and inspiration and gadfly, and to the future generations who seek to understand how we have become what we are (and how we might escape a fate that awaits those who cannot reflect on history and its implications, or desire to remove evidence from policy and cruise on their prejudices).